When the Ship Becomes the System

What The Sea Wolf (1941) teaches about power, myth, and the people trapped inside

⚠️ SPOILERS: This review contains full-plot discussion.

The Ghost appears through fog. Black-and-white, luminous. A sealing schooner. Already organized. Already governed. The camera finds Humphrey Van Weyden in the water—literary critic, survivor of shipwreck, accustomed to salons and theory. He surfaces into a world that doesn’t care what he thinks about anything.

Captain Wolf Larsen pulls him aboard. Not rescue. Acquisition.

This isn’t a story about the sea. It’s a study of what happens when one person decides hierarchy is “natural”—and calls it truth.

Authority Without Legitimacy

Larsen rules by force, not consent. Nobody voted. Nobody chose this captain, this crew configuration, these rules. The ship departed port with power already allocated. Order becomes “necessary,” cruelty becomes “efficient,” and punishment stops looking like a decision at all.

Watch how it works: A man fails at rope work. Larsen doesn’t argue philosophy. He applies consequences. The crew doesn’t debate justice. They calculate survival. Within days, Van Weyden stops appealing to rights he remembers from shore. The ship has different physics.

Systems survive longest when they convince people that power isn’t imposed—it’s inevitable.

Workplaces that call control “accountability.” Platforms that rename manipulation “personalization.” Leaders who confuse dominance with strength. The mechanism remains the same. Only the terminology updates.

The Myth of the Self-Made Titan

Larsen lectures Van Weyden about philosophy. The strong survive. Morality is weakness. Compassion is sentimental. He gestures at Nietzsche and clings to Milton—not because he understands either, but because they let his brutality wear a costume.

Edward G. Robinson plays this contradiction like a string pulled too tight. Watch his hands cradle books with genuine hunger. Watch his face harden when challenged. He makes Larsen both reader and predator—a man who quotes poetry while calculating consequences. The performance shows how intelligence serves power instead of questioning it.

But look beneath:

He’s isolated. He depends entirely on the crew he despises. His “strength” is actually fragility wearing armor. He reads literature obsessively. His headaches increase. His body fails him. The system he embodies is consuming itself from within.

When systems glorify the “great individual,” they hide how dependent that individual is on invisible labor. Larsen doesn’t sail the Ghost alone. He just claims sole credit. The seals don’t catch themselves. The ship doesn’t navigate itself. But the mythology requires pretending the individual is everything and the structure is nothing.

Culture as Resistance

Then something shifts. Ideas enter the ship. Books. Conversation. Memory of other possibilities. Ruth Brewster arrives—writer, survivor, practiced in thinking clearly under pressure. She and Van Weyden read poetry. They discuss literature. They imagine futures beyond the horizon.

They don’t overthrow Larsen. They don’t mutiny. They simply maintain an alternative reality inside the one he controls.

Watch his reaction. Not indifference. Fear. He mocks them. Interrupts them. Assigns them separate duties. Culture can domesticate as easily as it frees—but on the Ghost, it becomes oxygen, because systems fear culture. Culture creates alternative realities—and therefore, alternative loyalties. The conversations threaten him more than physical resistance would. You can punish bodies. You can’t punish imagination.

The ship remains his. But the absolute nature of his authority fractures—not through rebellion, but through imagination.

The Ship as Laboratory

Step back. Closed environment. Hierarchies fixed. Stakes high. Death possible. Escape unlikely.

Who adapts? The cook becomes useful. The crew learns which silences keep them safe. Van Weyden develops muscles he didn’t know he could build—not because he believes in Larsen’s philosophy, but because survival inside a system requires learning its language.

Who breaks? The men who couldn’t calculate fast enough. The ones who expected fairness. The ones who thought their previous status would transfer.

Who refuses? Ruth maintains her identity as writer. Van Weyden keeps reading. Small acts. Mostly invisible. Preservation nonetheless.

What happens to bystanders? They become participants. Silence becomes complicity. Witness becomes involvement. The ship allows no neutral position.

The Sea Wolf is not a hero story. It’s a study of survival inside systems that were broken before you arrived.

Collapse Without Victory

When the system collapses, nobody “wins.”

Larsen’s body fails him. Paralysis. Blindness. The titan becomes dependent on the people he tormented. The ship rots. The crew scatters. Van Weyden and Ruth escape to an island—but they carry the Ghost with them—in how they watch for threats, how they organize labor, what they cannot forget.

Systems don’t just fail. They leave residues—habits of fear, silence, obedience—that live on long after the ship sinks.

The film understands this. No triumphant music. No speech about freedom. Just two people on a beach, watching the wreckage, trying to remember what normal felt like.

Why This Film Still Matters

The Ghost appears everywhere. In workplaces where one person’s “vision” justifies everyone else’s exhaustion. In politics where “strong leaders” promise order through dominance. In online platforms that call algorithmic control “curation.” In personality cults that confuse charisma with competence.

The mechanism remains the same. The ship just gets larger. The fog just gets thicker.

The Sea Wolf reminds us that the most dangerous tyrants aren’t the ones shouting orders—they’re the ones who convince us that their world is the only one possible.

The Ocean and the Ship

The film ends with water. Vast. Indifferent. Containing infinite possibility. The Ghost sinks into it—one structure among thousands that thought themselves permanent.

The ocean doesn’t care about Larsen’s philosophy. It doesn’t validate it, doesn’t refute it. It simply continues.

And there, on that island, two people who survived begin asking different questions. Not “Who rules?” — but “Why is the ship built this way at all?”

Ships can always be rebuilt. The question is whether we keep copying the same plans.

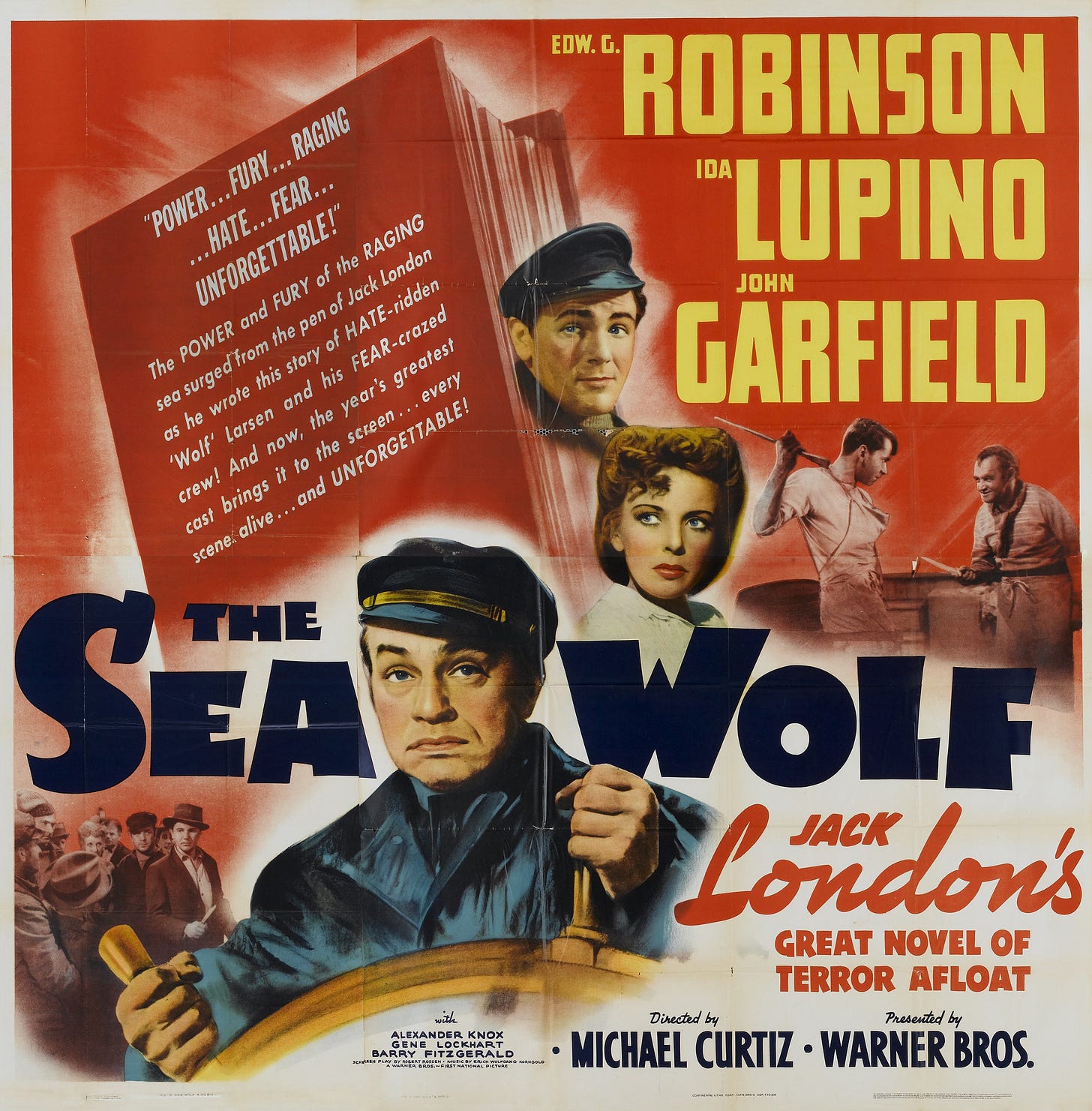

The Sea Wolf (1941), directed by Michael Curtiz, based on Jack London’s novel. Currently available through Warner Archive.

What keeps pulling me back to this film isn't the sea or the adventure—it's watching the *Ghost* become a laboratory for how systems break people.

The questions that won't let go:

When does authority stop needing justification?

At what point do the trapped stop imagining escape—and start believing the ship is all there is?

What I'm curious about:

**Who felt most trapped to you?** Van Weyden? Ruth? The crew? Larsen himself?

**Is Larsen a villain—or just what happens when a system rewards domination and calls it strength?**

**Where do you see the *Ghost* operating today?** What systems feel like ships you can't leave?

I'd like to hear what you saw.