When the story blames the king, the system survives untouched—and it will do it again.

We explain institutional collapse by diagnosing leaders—because diagnosing systems is harder, slower, and more dangerous.

I. The Wrong Story

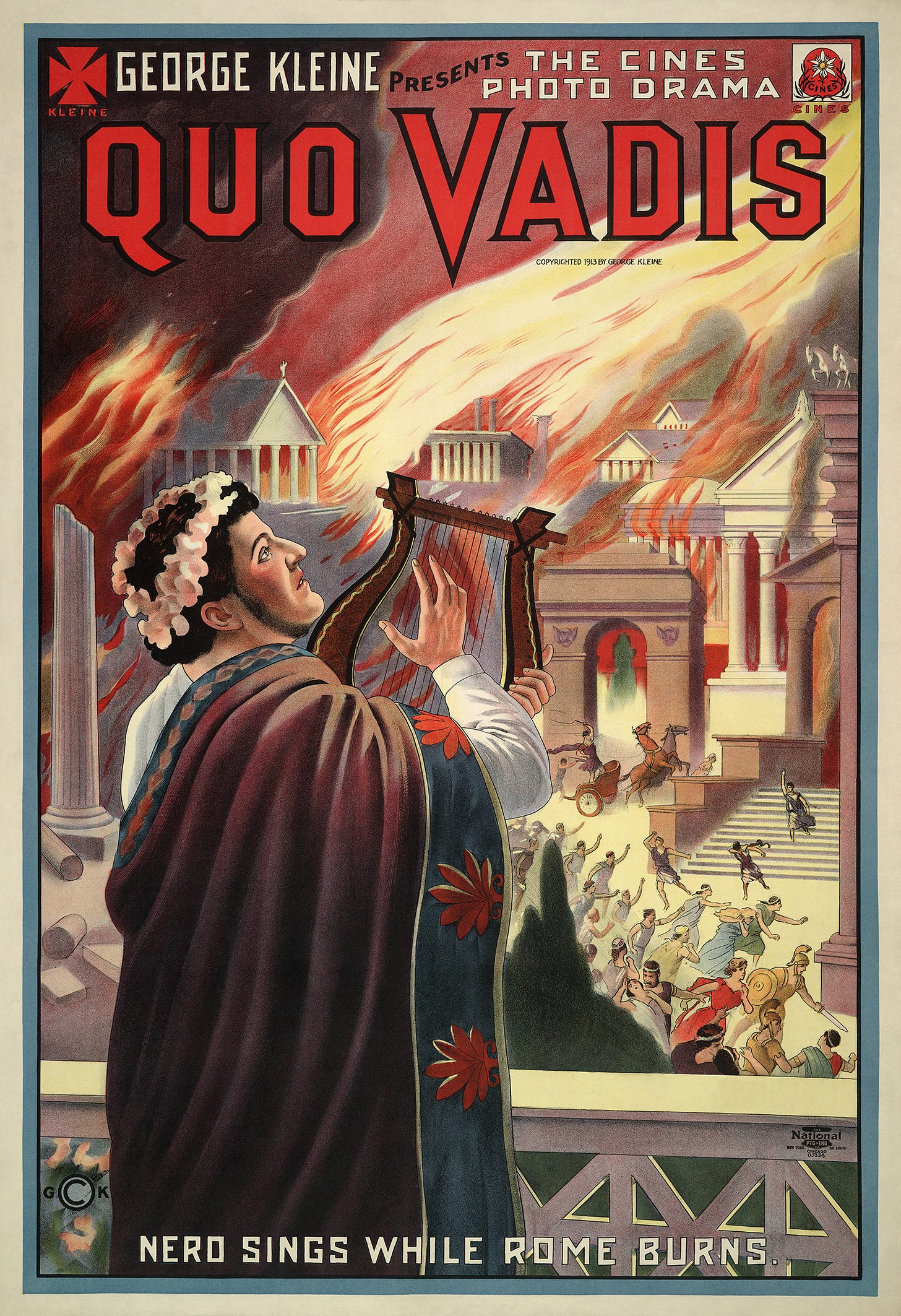

Poster_for_Quo_Vadis_(1913_silent_film)

Rome, 64 CE. The city burns for six days. Nero—emperor, poet, performer—reportedly plays the lyre while watching flames consume entire neighborhoods. Later historians call him mad. Insane. A tyrant consumed by his own delusions.

The story we tell: One bad man. One broken mind. Remove the king, fix the empire.

The story we don’t tell: How did one man’s supposed madness commandeer the entire Roman administrative apparatus? Where were the generals, the senators, the bureaucrats, the advisors? What system allowed theatrical delusion to govern military decisions, tax policy, and infrastructure management for fourteen years?

What if the king isn’t the story? What if the interesting part is the system that let him rule like this?

II. The Myth: Blame the King, Save the System

We love simple explanations. One villain. One flaw. One head to remove and the body politic heals itself. It’s clean. It’s satisfying. It preserves the belief that institutions are fundamentally sound—they just need better personnel.

Empires justify collapse by pinning it on personalities. Rome fell because of Nero, Caligula, Commodus—not because of currency debasement, overextended military commitments, and administrative rot. France collapsed because Louis XVI was weak—not because the entire fiscal system had become unmanageable decades before he took the throne. Russia fell because Nicholas II was incompetent—not because the Tsarist system had been hollow for generations.

The “mad king” narrative protects institutions from examination. If the problem is one person’s psychology, the solution is simple: better recruitment, better succession, better character. The architecture stays intact.

But systems don’t fail because of one bad man. They fail because feedback stops working.

The “mad king” story isn’t a mistake. It’s a stabilizing myth. It protects institutions by isolating failure in a single, disposable body.

When truth cannot travel upward, when institutional correction mechanisms break, when the people closest to power learn that survival requires lying—you get rulers who appear irrational. Not because they’re clinically insane, but because they’re operating on completely fictional information inside systems designed to hide reality.

III. Louis XVI and the Silence of the Court

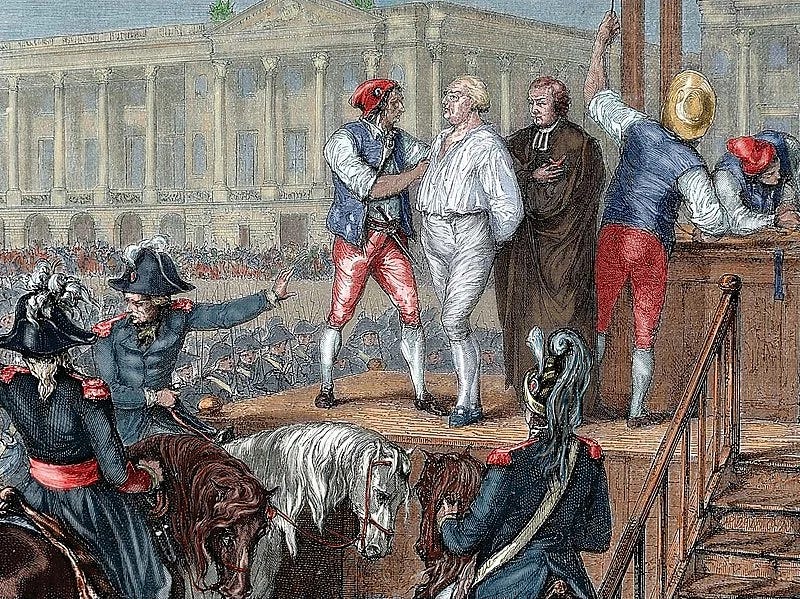

The execution of Louis XVI in 1793

This isn’t cruelty. It’s what happens when information is filtered until urgency disappears.

France, 1780s. The treasury is empty. Bread prices spike. Peasants starve while the court at Versailles consumes 6% of the national budget on palace maintenance, staff salaries, and royal ceremony.

Louis XVI isn’t cruel. He’s not a sadist. By most accounts, he’s mild-mannered, interested in locksmithing, uncomfortable with confrontation. He doesn’t want people to suffer.

But he doesn’t know they’re suffering. Not really.

The mechanism: bureaucratic blindness. Information travels up through layers of courtiers, ministers, advisors—each layer motivated to soften bad news, emphasize successes, avoid being the messenger who gets blamed for problems they didn’t create. By the time reality reaches the king, it’s been translated into bureaucratic language that strips urgency, context, and truth.

The Controller-General reports revenue projections that assume good harvests. The Master of Ceremonies reports that protocol was observed flawlessly. Nobody reports that bread riots are spreading because nobody wants to be the person who ruins the king’s day.

The king wakes at 8:00 AM for the Grand Lever—the ceremonial waking attended by dozens of nobles competing for the honor of handing him his shirt. He eats meals in public. He attends Mass. He reviews reports formatted in the language of continuity and competence. Everything feels normal because the entire system is designed to feel normal.

When Louis finally understands that France is days from bankruptcy, weeks from revolution, he seems paralyzed. Indecisive. Weak. Mad, even—how could someone not see this coming?

But he couldn’t see it. The system ensured he couldn’t.

When truth cannot travel upward, “madness” is just ignorance wearing a crown.

IV. Nicholas II and the Fear Loop

Glorification of Emperor Nikolai Romanov as a Saint

This is what fear does to feedback.

Russia, 1905. Peaceful protestors march to the Winter Palace to petition the Tsar. The Imperial Guard opens fire. Hundreds dead. Thousands wounded. “Bloody Sunday” triggers revolution.

Nicholas II didn’t order the massacre. He wasn’t even in the city. But he also didn’t know the march was happening, didn’t understand the scale of discontent, didn’t realize his government had become so detached from popular sentiment that soldiers would fire on unarmed civilians carrying icons and portraits of the Tsar himself.

The mechanism: the fear loop. Fear as governing tool.

Nicholas ruled through a security apparatus—the Okhrana—that made careers by finding threats. Governors, police chiefs, and ministers advanced by demonstrating loyalty and eliminating dissent. Honesty became dangerous. If you reported that peasants were suffering, you risked being labeled sympathetic to revolutionaries. If you suggested reforms, you risked being seen as weak. If you told the Tsar that policies weren’t working, you risked being replaced by someone who would say they were.

So nobody did. Everyone around Nicholas learned the same lesson: survival equals loyalty, not accuracy.

The Tsar heard that order was maintained, borders were secure, the people loved him. He heard that strikes were the work of foreign agitators, not systemic problems. He heard that military strength was unmatched, right up until Japan destroyed the Russian fleet in 1905.

Each lie made the next disaster worse. By 1917, when the entire edifice collapsed, Nicholas seemed delusional—signing orders that nobody followed, issuing proclamations that nobody believed, unable to grasp that the empire had already ended.

The system manufactured delusion.

When truth cannot travel upward, power loses contact with reality.

V. Mao’s Great Leap Forward and the Optimization Trap

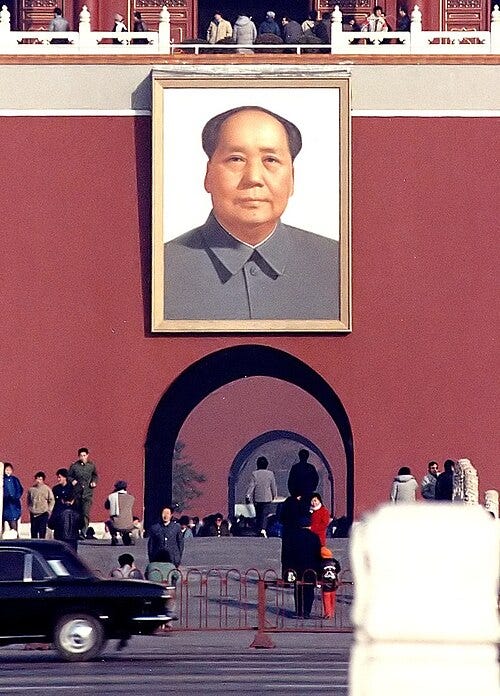

Tiananmen Portrait of Mao Zedong

This is what happens when targets replace truth.

China, 1958-1962. Mao Zedong launches the Great Leap Forward—ambitious plan to industrialize China overnight through rural steel production and collective farming. The result: famine kills tens of millions.

The standard story: Mao was ideologically rigid, disconnected from reality, unwilling to admit failure.

The mechanism: the optimization trap. Central plans override lived reality.

The Party set quotas. Provincial officials reported meeting them—by melting down farming tools in backyard furnaces that produced useless pig iron. Local officials reported record harvests—by taking grain from peasant reserves, from seed stocks, from anywhere they could find it.

At every level, survival depended on meeting targets. The person who reported actual conditions—crop failure, starvation, systemic breakdown—got blamed for sabotaging the revolution. The person who reported success got promoted.

Mao received reports of record harvests while millions starved. Not because he refused reality—but because the system made reality invisible. Every feedback mechanism rewarded performance theater.

When evidence of famine finally reached central authorities, the response wasn’t to question the plan—it was to blame local implementation, find scapegoats, and demand renewed commitment to quotas.

The “mad king” wasn’t one man’s ideology. It was a machine that punished truth until the theater consumed millions of lives.

VI. Saddam Hussein and Useful Madness

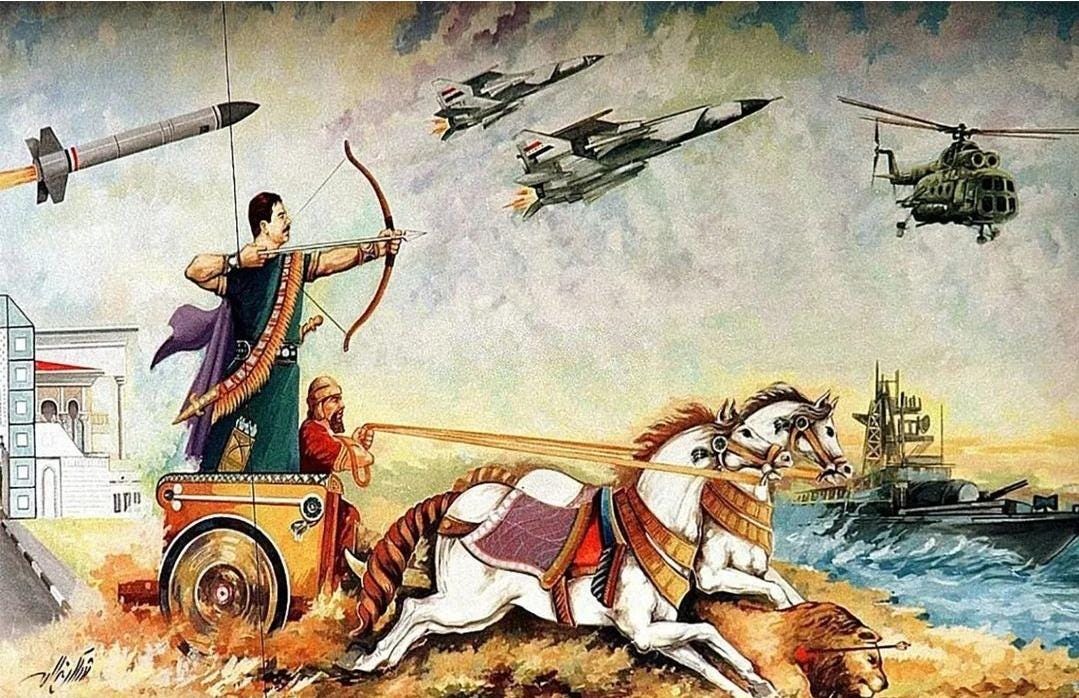

Saddam Hussein in the likeness of an Mesopotamian king

This is what happens when unpredictability becomes policy.

Iraq, 1979. Saddam Hussein takes power. Within days, he gathers the Ba’ath Party leadership for a special assembly. He reads a list of names. As each name is called, armed guards escort the person out of the room. Sixty-eight people disappear. Many are executed. The survivors learn: proximity to power is lethal without absolute loyalty.

The mechanism: useful madness. Power learns to reward unpredictability.

Saddam ruled through calculated instability. Purges weren’t random—they were strategic. Advisors never knew which policy position would get them killed. Generals couldn’t predict whether success would be rewarded or interpreted as threatening. Ministers understood that today’s correct answer might be tomorrow’s treason.

The chaos wasn’t a bug. It was a feature.

Unpredictability keeps rivals off-balance. If subordinates can’t predict what will anger the leader, they can’t coordinate against him. If loyalty is measured by willingness to endure arbitrary violence, then survival requires constant performance of submission. If “madness” means nobody can safely tell you “no,” then madness becomes rational strategy for maintaining power.

Saddam appeared irrational when he invaded Kuwait in 1990—bad military strategy, predictable international response, obvious disaster. But he’d built a system where nobody could tell him it was a bad idea. The generals who might have objected had watched colleagues get executed for smaller disagreements.

By the time he made catastrophic decisions, the system that could have corrected him had been deliberately destroyed.

Sometimes the system survives by making the king terrifying.

VII. The Selection Mechanism

Pull the threads together. Across Rome and France and Russia and China and Iraq, the pattern repeats:

These aren’t historical quirks. They’re repeatable failure modes.

Truth cannot travel upward. Institutional incentives punish honesty. The people closest to information learn that career survival requires selective reporting. By the time reality reaches decision-makers, it’s been filtered through layers of self-protection until it’s unrecognizable.

Loyalty replaces competence. When systems can’t distinguish between accurate information and sedition, they optimize for the latter. The advisor who says “this policy is failing” looks identical to the advisor who wants to seize power. Safer to promote yes-men than risk traitors.

Institutions hollow out. Formal structures persist—ministries, departments, councils, protocols. But they stop doing the work they were designed to do. They become performance spaces where people act out institutional roles while actual governance happens through informal networks and whoever currently has the king’s ear.

The ruler becomes the face of a deeper failure. When collapse comes, we remember Nero’s fiddle, Louis’s indecision, Nicholas’s stubbornness, Mao’s ideology, Saddam’s brutality. We don’t remember the centuries of institutional decay that made their reigns possible. We don’t remember the thousands of officials who knew better and said nothing.

Ask one question early: who gets punished for being right too soon?

Think beyond politics. Enron didn’t collapse because of one “mad CEO.” It collapsed because performance theater was rewarded, honesty was punished, and entire departments learned to fake numbers to survive. The faces changed. The incentives didn’t. The same pattern appears anywhere metrics replace reality.

The king isn’t breaking the system. The broken system is building the king.

VIII. Why This Matters Now

We keep looking for the next “mad king.” The leader whose personality explains everything. The individual whose removal would solve systemic problems. The personality disorder that accounts for institutional failure.

It’s tempting. It’s simple. It preserves our faith in structures.

But the real danger isn’t individual pathology. It’s:

Fragile institutions that can’t absorb correction. Systems that break when anyone questions core assumptions. Organizations that treat feedback as betrayal.

Reward structures that punish honesty. When truth-telling damages careers more reliably than failure damages organizations, truth stops flowing. When admitting problems is more dangerous than hiding them, problems multiply in darkness.

Systems that cannot self-correct. Institutions that have lost the ability to distinguish between loyal opposition and existential threat. Organizations where every challenge to current practice looks like sabotage. Governments where competence is suspect and agreement is proof of fitness.

These conditions aren’t exotic. They’re not limited to empires or dictatorships or distant history. They emerge whenever feedback mechanisms break. Whenever the gap between formal accountability and actual consequences grows wide enough. Whenever people learn that survival requires performance instead of accuracy.

Individuals matter—but systems decide which individuals rise, which survive, and which are believed.

IX. Watch the System

Forget the king. Watch the system. When you want to assess institutional health, ask different questions:

Who can say “no”? Not in theory—in practice. When someone with expertise contradicts current policy, what happens to them? Do they get promoted for catching problems early, or do they get reassigned to positions where they can’t cause trouble? If the answer is the latter, you’re watching feedback mechanisms break in real time.

Who controls information? How many layers exist between ground truth and decision-makers? How many opportunities for filtering, sanitizing, or burying data? What incentives shape how information travels upward? If bad news consistently arrives late, softened, or not at all—the system is already compromised.

What happens to people who tell the truth? Track careers. Do people who identify problems early get rewarded or punished? Do whistle-blowers get protected or destroyed? Do internal critics get listened to or eliminated? If honesty damages careers more than incompetence, you’re not watching individual failure—you’re watching systemic collapse in progress.

If those answers are bad, the king doesn’t matter. Collapse is already underway. The personality at the top is just the visible symptom of institutional rot that’s been progressing for years or decades.

X. The Scene Again

Rome, 64 CE. The city burns. Nero plays music. Later generations call him mad.

But reinterpret: A signal light flashing on a dashboard that nobody wanted to read. An emperor surrounded by people who learned that challenging him was more dangerous than letting him perform. A system that had spent decades selecting for courtiers who could smile through disaster. An empire that had confused ceremony with governance so thoroughly that when crisis came, ritual was all anyone knew how to do.

Not a mad king—a mad system, producing kings in its own image.

If you wait until the king looks mad, the system has already been broken for a long time.

And when the story blames the king, the system survives untouched—and it will do it again.

Most collapse stories start with personality.

This one starts with incentives.

When institutions stop letting truth travel upward, leaders don’t need to be evil—or even especially incompetent—to look mad. They’re operating inside a system that punishes accuracy and rewards performance.

If you want to understand failure before it gets personalized, watch who gets punished for being right too soon.

Phenomenal framing of how feedback loops determin institutional health way more than individual psychology. The question about who gets punished for being right too soon is the most practical diagnostic tool I've seen for this. I worked at a compnay where people learned to stop flagging problems early because it made you look like you were creating drama, and within two years the whole org was running on fantasy metrics. That line about systems not failing because of one bad person but because feedback stops working should be posted in every boardroom.