This isn’t a story about nostalgia or labor folklore. It’s about what happens when a system discovers it can run on people, the way a mill runs on timber. The Industrial Workers of the World didn’t just organize strikes. They tried to redesign the architecture of work—and the system answered.

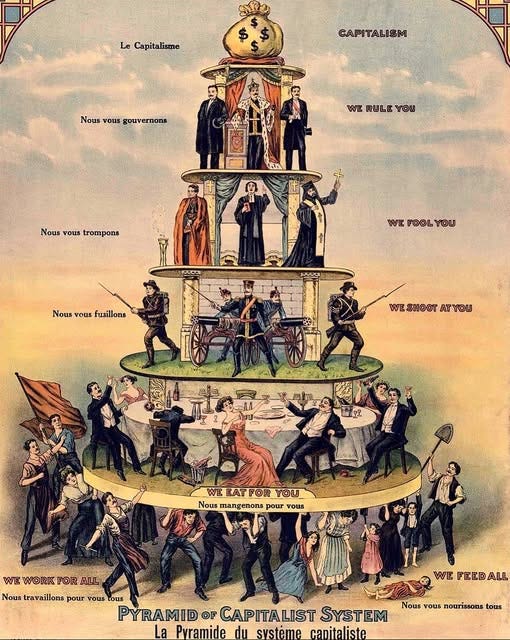

The Pyramid of Capitalist System (1911 Poster)

I.

Everett, Washington. November 5th, 1916. Sunday morning.

The steamship Verona cuts through Puget Sound fog, two hundred and fifty men crowded on her deck. They are singing. Not marching songs—work songs. Logging songs. The kind you sing when your hands are bleeding and the foreman is watching and singing is the only thing they can’t take from you.

They are Wobblies. Members of the Industrial Workers of the World. They have come to speak. The city has made speaking illegal.

The dock comes into view. Two hundred deputies wait in formation. Sheriff Donald McRae at the front. Lumber company guards mixed with citizens armed that morning by men who own the mills. Rifles visible. Crowd silent.

Fifty feet from the pier, someone fires. Later, no one will agree who.

Then everything fires.

Five minutes. Two hundred rounds. Men diving into cold water. Men falling on deck. Blood spreading across wet wood. At least seven dead. Dozens wounded. The Verona’s captain spins the wheel hard, turning back toward Seattle, engine grinding, deck slippery with blood and seawater.

The men still standing are still singing.

This is not the beginning of the story. This is the moment the story breaks open.

A factory doesn’t collapse in one day. It collapses in the lungs, in the hands, in the rent due on Friday. It collapses in the father who comes home too tired to speak and the child who learns that work is what kills you slowly. It collapses in the woman at the textile machine whose fingers move faster than thought because thought slows the line and the line cannot slow.

By 1916, American workers had lived inside this collapse for a generation. They had watched productivity double while wages stayed flat. They had watched their neighbors lose fingers, lungs, lives. They had watched courts rule that corporations were persons but persons were parts.

The Wobblies felt inevitable because the alternative had become unbearable.

This is not a story about martyrdom or lost ideals. It is a case study in systems design. For a brief moment, American workers built an organizational structure that neutralized fragmentation—the core control mechanism of industrial capitalism. What follows is not heroism, but proof. And how the system responded to that proof.

II. What They Actually Tried to Build

The Industrial Workers of the World, founded Chicago, 1905, was not another union.

Other unions organized by craft. You were a carpenter or you were nothing. You were a skilled machinist or you were nothing. You were white, male, native-born, or you were nothing.

The IWW organized by industry. One mill, one union. One mine, one union. Timber workers and mill workers and dock workers—all workers, one class, no internal hierarchies.

This seems simple now. It was not simple then.

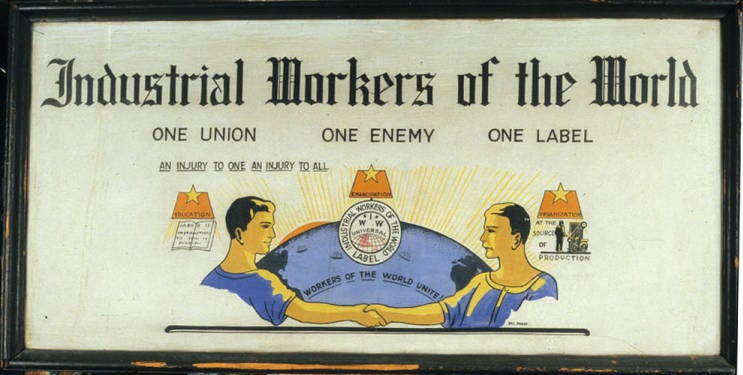

The IWW is Coming - Join the One Big Union

The American Federation of Labor, the dominant union federation, had spent twenty years building walls. Skilled workers versus unskilled. Native versus immigrant. White versus Black. Men versus women. Each wall created a market advantage for those inside. Each wall created a pool of desperate labor outside willing to work for less.

The IWW said: One Big Union.

They meant it structurally. Every worker in an industry belonged to the same organization with the same power and the same vote. A timber faller in Oregon had the same standing as a mill hand in Louisiana.

They meant it racially. The IWW organized Black workers in the South when doing so meant beatings and jail. They organized Chinese and Japanese workers on the West Coast when other unions were demanding their exclusion. They organized women in textile mills when the AFL wouldn’t let women through the door.

They meant it politically. Direct democracy in every local. Decisions made by those who would live with the consequences. No permanent officials accumulating power. No contracts that traded militancy for recognition.

Where the Knights of Labor imagined broad solidarity, the IWW tried to build it into machinery. This was systems thinking before systems language existed.

The IWW looked at industrial capitalism and saw a machine designed to fragment human beings, then optimize the extraction rate until they wore out.

Their counter-design was equally structural: integrate the parts back into persons, then integrate the persons into collective power that couldn’t be fragmented.

One Big Union wasn’t a slogan. It was architecture.

III. The Mechanism They Were Fighting

Fragmentation as Control

The system divided to survive.

In 1919, Chicago’s meatpacking plants employ fifty thousand workers. Twenty-three languages spoken on the kill floor alone.

Management posts hiring notices in Lithuanian at the Lithuanian church. In Polish at the Polish social club. In Italian at the Italian mutual aid society. When white workers strike, they hire Black workers from the South. When Black workers organize, they bring in Mexican workers. When men demand higher wages, they hire women at half the rate.

Each group is told the same thing: the people next to you want your job. They’ll work for less. They’ll cross your line. They already have.

The story works because the structure makes it true. The skilled butchers have a union that excludes the unskilled gut workers. The white workers have contracts that exclude Black workers. The men have agreements that exclude women. Each fragment protects its position by keeping others out.

Stand on the factory floor. Listen. Twenty-three languages. Everyone working. No one speaking. Each worker competing with the worker beside them, neither able to see the foreman timing them both.

If the story convinces you your enemy is sideways, you never look up.

Management didn’t need to invent racism or nativism or sexism. Those systems already existed. Management simply needed to make them profitable. Give the skilled workers five cents more than the unskilled. Give the white workers ten cents more than the Black workers. Give the native-born workers seniority over the immigrants.

The fragments would police themselves.

Optimization Without Care

Industrial capitalism optimized for three metrics: output, compliance, predictability.

It did not optimize for health, dignity, or agency. Those variables were externalities.

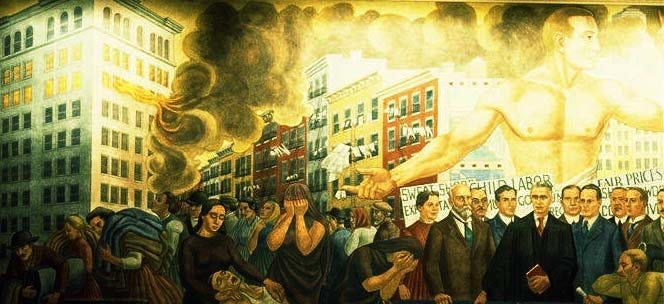

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, New York, March 25th, 1911.

Four forty-five in the afternoon. Eighth floor. Someone’s cigarette lands in a scrap bin. Fabric ignites. The fire spreads across oil-soaked floors faster than anyone can run.

The girls rush to the exits. The doors are locked. From the outside. Always locked, to prevent unauthorized breaks, to prevent fabric theft, to keep the line moving.

They run to the fire escapes. The iron collapses under their weight, sending bodies eight stories down.

They crowd the windows. The fire department ladders reach six floors. The safety nets—firefighters holding canvas sheets—tear when bodies hit from eight stories up.

Eighteen minutes. One hundred and forty-six dead. Mostly young women. Mostly Italian and Jewish immigrants. Some jumped. Some burned. Some suffocated against the locked doors.

The factory had been optimized. Workflow efficient. Productivity high. Compliance enforced. The doors were locked to prevent workers from taking breaks or stealing fabric.

Not metaphorically. Literally. The workers were part of the capital equipment. When they wore out, you replaced them.

The Triangle owners were indicted for manslaughter and acquitted. They later collected insurance money exceeding the compensation paid to victims’ families.

The system contained no error. It was functioning exactly as designed.

Meaning as Infrastructure

The IWW understood something other unions missed: whoever writes the story writes the limits of the possible.

So they wrote songs. They published pamphlets in twenty languages. They created rituals—the red card, the speaking tours, the free speech fights. They built a counter-narrative where workers were not parts but persons, not competitors but comrades, not lucky to have jobs but entitled to dignity.

The Little Red Songbook, first published 1909, eventually contained two hundred songs set to familiar tunes—hymns, patriotic anthems, popular ballads. Workers could learn them in one hearing and remember them forever. “Dump the Bosses Off Your Back.” “Solidarity Forever.” “The Preacher and the Slave.”

Management tried to disrupt meetings with noise. The Wobblies sang louder. Police arrested speakers on street corners. The Wobblies sent more speakers. Courts ruled public speaking illegal. The Wobblies went to jail singing and emerged singing.

Culture is infrastructure. Narrative is strategy. Solidarity is not natural—it must be built, maintained, defended, and reproduced.

Decades later, Woody Guthrie kept that work alive. His songs didn’t soothe—they named reality. Not entertainment, but counter-architecture: reminders that the problem wasn’t individual failure, but design. Arlo picked up the thread from another angle—showing how absurd the machinery felt from the inside, where bureaucracy becomes too senseless and too large to ever care about the people trapped inside it.

IV. When Solidarity Started Working

Between 1905 and 1920, the IWW won strikes that conventional unions said were impossible.

Lawrence, Massachusetts, January 1912.

The mill owners cut wages. Not by negotiation—by decree. The workers, twenty-three thousand of them, walk out. The American Federation of Labor says it won’t work. Too fragmented. Too many languages. Too many women. Too unskilled.

The IWW sends organizers who speak Italian, Polish, Lithuanian, Russian, Arabic, Hebrew, Portuguese, Syrian, German. They set up kitchens. They organize childcare. They publish strike bulletins in twenty-five languages daily.

The mill owners hire private guards. The guards attack picket lines. When that doesn’t work, the city declares martial law. The police arrest strikers—hundreds of them. When that doesn’t work, they arrest the children being evacuated to sympathetic families in other cities. Officers club mothers trying to put their children on trains.

The photographs make national news.

Ten weeks. The mills surrender. Wages rise. Hours fall. The impossible strike won because the IWW made solidarity operational.

The Mesabi Range, Minnesota, 1916. Iron miners, sixteen thousand strong, mostly immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. No formal union. No strike fund. The IWW sent organizers who spoke their languages and slept in their camps. Three months later, the mining companies agreed to negotiations.

Philadelphia longshoremen, 1913. Three thousand Black workers joined the IWW after being excluded from AFL unions. They struck for recognition and won.

What scared power was not the ideology. It was the evidence.

Solidarity worked.

Across race, language, skill level, gender—when workers acted as one unit, they had structural leverage that corporations couldn’t fragment.

The system’s primary defense mechanism—division—stopped functioning.

V. How Systems Defend Themselves

Systems defend themselves not because they are evil, but because they are built to preserve the flow of power.

The response to IWW success was structural, not personal.

September 5th, 1917.

Federal agents hit IWW halls in sixty cities. Simultaneously. Seattle. Chicago. New York. San Francisco. Spokane. Omaha. All at once. Same hour. Same warrants. Same charges.

They take membership lists. Financial records. Letters. Pamphlets. Typewriters. Printing presses. Everything.

One hundred and sixty-five leaders arrested. The trials are designed not to determine guilt but to drain resources. Every dollar spent on lawyers is a dollar not spent organizing. Every leader in court is a leader not on the picket line. The process is the punishment.

Everett was not an anomaly. It was strategy.

Centralia, Washington, November 11th, 1919. Armistice Day parade.

American Legion members march past the IWW hall. Someone fires. Four Legionnaires fall. In the chaos, no one agrees who shot first.

That night, they come for Wesley Everest. Drag him from the city jail while the sheriff looks away. Put him in a car. Drive to the Chehalis River bridge.

They castrate him first. Then hang him from the railroad trestle. While he’s still swinging, they shoot him. Multiple times. From multiple directions.

The coroner rules it suicide.

Bisbee, Arizona, July 12th, 1917.

Two thousand men with white armbands—deputized that morning by Sheriff Harry Wheeler—move through the copper mining town at dawn. They round up strikers. Sympathizers. Anyone on a list prepared by mining company managers.

Thirteen hundred men are marched at gunpoint to the baseball field. No charges. No trials. No process.

Cattle cars wait at the Warren depot. The men are loaded. Twenty-three boxcars. Packed tight. The train pulls out, heading east across the desert.

Sixteen hours later, the train stops in Hermanas, New Mexico. Middle of nowhere. No town. No water. No shade. The doors open. The men are told to walk.

The train returns empty.

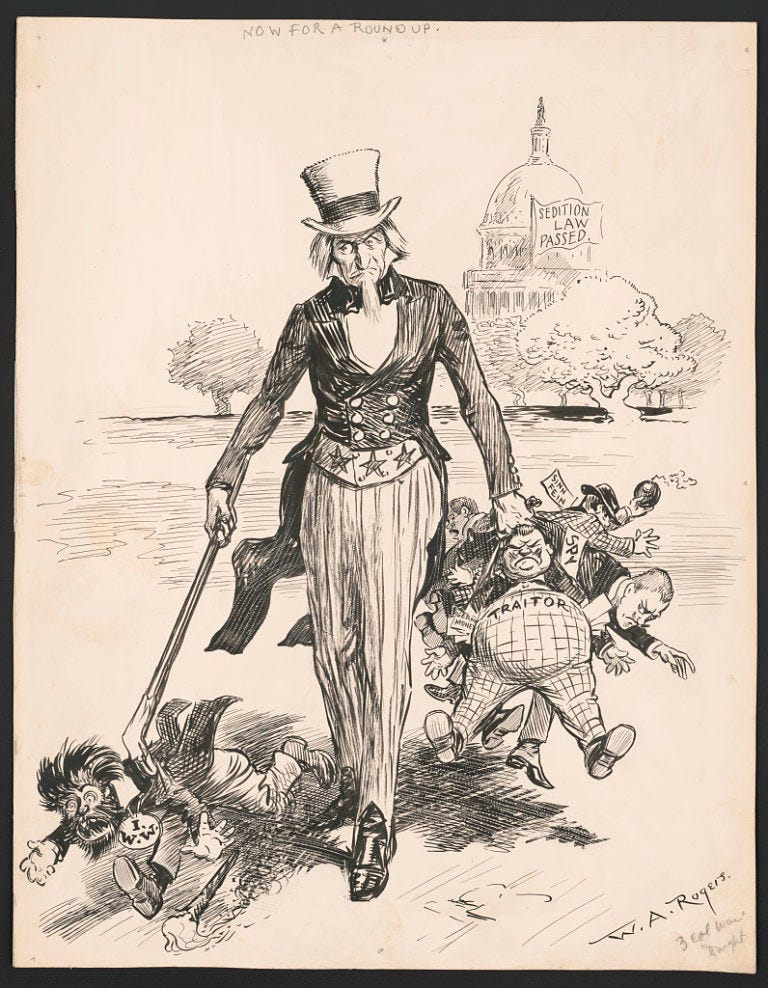

1918 political cartoon by William Allen Rogers, titled "Now for a round-up,"

The Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 made IWW organizing functionally illegal. Speaking against the war effort—which the IWW did, arguing that workers had no country—became a federal crime.

Repression worked because it changed the cost structure of solidarity. Joining the IWW in 1910 meant risking your job. Joining in 1918 meant risking deportation, prison, or death.

Meanwhile, corporations created company unions—organization without power, representation without leverage. The structure looked like democracy. The function was compliance.

Management also learned. They raised wages. They shortened hours. They installed safety equipment. Not because they discovered ethics, but because the IWW had demonstrated that workers who couldn’t be fragmented couldn’t be controlled.

The reforms came after the threat was neutralized.

VI. Why They Lost

The IWW didn’t lose because they were naïve. They lost because the system made solidarity more expensive than submission.

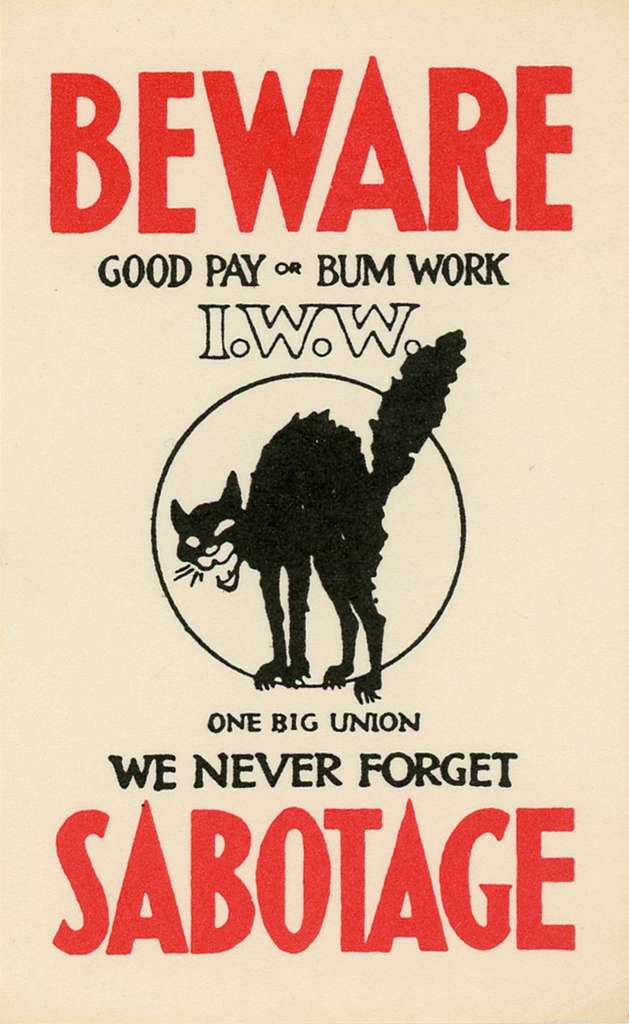

IWW sabotage cat

A skilled worker in 1920 could join an AFL craft union and negotiate a contract that gave him advantages over unskilled workers, women, Black workers, immigrants. He could protect his family. He could buy a house. He could send his children to school.

Or he could join the IWW and risk everything for the principle that all workers should have equal power.

When survival is at stake, people choose survival. That isn’t weakness. It’s incentives.

The system did not defeat the IWW by argument or reform. It defeated them by restructuring survival so that solidarity became a luxury good.

The IWW membership peaked around 150,000 in 1917. By 1925, it had collapsed to fewer than 30,000. The organization survives today, but as a historical memory more than a material force.

None of this means the IWW was flawless. Internal faction fights, inconsistent strategy, and a tendency to overestimate how far workers would go under repression all mattered. But those failures were secondary. The decisive force was structural: the system successfully made solidarity more expensive than submission.

This is not hero worship. It is diagnosis.

VII. Why They Still Matter

Amazon warehouse, Bessemer, Alabama, 2021.

Six thousand workers, majority Black, vote on whether to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

The company responds with precision. Anti-union consultants flood the facility—dozens of them, wearing Amazon vests, stationed at every break room, every entrance, every place workers gather. They hold mandatory meetings. Every shift. Every department. Attendance tracked.

Text messages arrive on workers’ phones. Individual messages. Personalized. “We heard you have concerns.”

In the parking lot, Amazon installs a mailbox. United States Postal Service box, but positioned where security cameras can record everyone who uses it. Where managers can watch who votes, when, and note who doesn’t.

The National Labor Relations Board later rules this constitutes illegal interference.

The vote fails anyway. 738 for unionization. 1,798 against.

Two years later, after the NLRB orders a re-vote, the same machinery runs again. The vote fails again.

The mechanism refined. The outcome unchanged.

Platform labor. Warehouse labor. Gig work. Creator economies. The structure is the same: fragment workers into competing individuals, optimize extraction rates, manage the narrative, make solidarity expensive.

You’re not an employee—you’re an “independent contractor.” Not a worker—a “creator.” Not a class—”entrepreneurs.” Flexibility replaces rights. Freedom replaces security.

One Big Union wasn’t utopian. It was a counter-architecture to a machine that treats humans as parts.

What the Wobblies understood:

Solidarity is infrastructure. It must be built deliberately because the default state of capitalism is fragmentation.

Narrative is strategy. The stories people tell about work determine what they think is possible.

Systems don’t change politely. Power concedes nothing without structural pressure.

The IWW failed to build an alternative that could survive state repression. But they succeeded in proving that the alternative was structurally viable. For fifteen years, workers across race, language, gender, and skill level demonstrated that they had more leverage together than apart.

The system learned from that proof. Which is why the architecture of modern work evolved in ways that make its recurrence unlikely.

Recent cases indicate the architecture can shift: Starbucks organizing across hundreds of stores, hotel workers strikes in multiple cities. Not revolution. Just evidence that people still remember how leverage works.

VIII.

"An Injury to One Is an Injury to All".

The IWW asked: What if everyone who works belongs?

Not as aspiration. As design principle.

They built an organization where a timber faller in the Pacific Northwest and a textile worker in Massachusetts had equal standing. Where a Black dockworker and a white miner belonged to the same union. Where decisions were made by those who would live with the consequences.

They proved it could function.

The question for us is harder: What kind of system needs people to forget that?

What kind of system requires workers to believe that the person next to them is the threat? What kind of system depends on people accepting that flexibility means no sick leave, that entrepreneurship means no labor protections, that freedom means isolation?

The answers are not mysterious. They are structural.

A system optimized for extraction requires fragmentation. A system optimized for compliance requires people to forget they were ever anything but parts.

The most successful systems do not eliminate alternatives. They make them expensive to remember. The IWW demonstrated that fragmentation was not inevitable. The system responded by ensuring that any future attempt would require people to risk more than most can afford. Forgetting was not accidental. It was engineered.

Oh, my. This has needed to be said just so for a very long time. Was just speaking some of this history to my son the other day. Most folks don't know, can't see it as they did then, because they're told an entirely different story every day. "The story works because the structure makes it true." McLuhan's "a chicken is an egg's idea of making more eggs."

"Culture is infrastructure. Narrative is strategy." How this is conceived and used makes all the difference. Compare the Tzotzil people you mention in another article to Americans/Canadians. "A system optimized for extraction requires fragmentation." A fundamental truth, and one reflected in the the current system's reliance on (and creation of) biological monocultures, as well as the social effects.

Thanks for this.

This framing of the IWW as systems architecture rather than just labor history is really sharp. The part about how fragmentation is the control mechanism hits hard, especially seeing how the same playbook gets used with platform labor today. What's fascinating is that the system didn't just crush the Wobblies through violence, it made solidarity itself unaffordable which is a way more durable defense. Everytime I see Amazon or Uber structure things so workers compete with eachother instead of coordinating, it's the same damn machine.